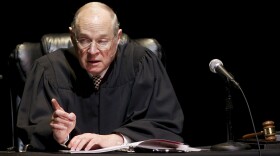

Read Justice Anthony Kennedy's majority opinion closely enough and you'll find an idea that shines like a beacon in guiding him to his destination in the Defense of Marriage Act case: dignity.

The concept appears no less than nine times in the landmark 26-page decision overturning the 1996 law blocking federal recognition of gay marriage. It's not the first time he's rolled it out to explain his views on the protections guaranteed by the Constitution. A decade earlier, Kennedy referred to the "dignity of free persons" in his majority opinion in another landmark case that voided a Texas law targeting gay citizens by criminalizing sodomy.

His notion of human dignity explains a lot about how the California-born justice has come to be referred to by some observers as " ." And it helps illuminate his uneasy relationship with his conservative colleagues.

Justice Antonin Scalia, for one, described Kennedy's rationale in the DOMA case as "rootless and shifting," an opinion larded with moral superiority that painted DOMA supporters as "unhinged members of a wild-eyed lynch mob."

Kennedy's Concept

Kennedy provided a telling preview of his perspective at his 1988 Senate confirmation hearing, when he referred to a right to human dignity.

When asked his view of factors that determine what the Constitution protects under the concept of liberty, Kennedy, a Reagan appointee, responded: "A very abbreviated list of the considerations are: the essentials of the right to human dignity, the injury to the person, the harm to the person, the anguish to the person, the inability of the person to manifest his or her own personality, the inability of a person to obtain his or her own self-fulfillment, the inability of a person to reach his or her own potential."

In 1996, as the author of the majority opinion that struck down a Colorado constitutional amendment that denied anti-discrimination protections to gay and lesbian residents, Kennedy seemed to begin sketching the outline of his view of human dignity as it relates to gay rights.

"A state," he wrote, "cannot so deem a class of persons a stranger to its laws."

By 2003, he offered a much fuller portrait in the Texas case where he referred to the "dignity of free persons" and to a court precedent that "demeans the lives of homosexual persons."

In the DOMA opinion, says Jeffrey Rosen, president and CEO of the National Constitution Center, Kennedy's "twin concerns for the dignity of the individual and the dignity of states converged."

At the heart of liberty is the right to define oneself, and that concept of personal autonomy "is centrally connected to dignity in Justice Kennedy's mind," says Rosen, also a law professor at George Washington University.

Catholic, Or catholic?

Some scholars, including Frank Colucci, have theorized that Kennedy's Catholicism informs his judicial concept of dignity.

But Colucci, author of Justice Kennedy's Jurisprudence: The Full and Necessary Meaning of Liberty, says he's stepped back a bit from his book's assertion that the justice's conception of human dignity has some roots in the vigorous post-Vatican II conversations about the church and its place in the modern world.

"That's more speculative," Colucci says. "But he fundamentally does see the Constitution as protecting liberty, and that means not having it infringe on people's lives."

"The concept of dignity is something that's run through many of his opinions, and not just in this area," he says.

In Colucci's view, Kennedy's jurisprudence yokes the constitutional concepts of liberty and equality, and "ties them to the larger consideration of the individual person and how they can best live their lives, and how that's protected by government."

Beyond Gay Rights

Kennedy's stances have been a source of puzzlement to court watchers.

Now the key swing vote in his 25th year on the court, he has infuriated Scalia and conservatives at times, but libertarians like Ilya Shapiro, editor-in-chief of the Cato Institute's Supreme Court Review, dismiss efforts to portray Kennedy as one of their kind.

Shapiro has referred to the justice as a "fainthearted libertarian at best," and a "sui generis enigma at the heart of the modern Supreme Court."

But Colucci argues that Kennedy's concept of liberty and dignity across issues can be tracked in cases the high court decided just this week.

In supporting the narrowing of terms under which public colleges and universities can use race-based considerations in admissions, Kennedy was advancing his concept of keeping government out of the business of defining individuals, Colucci says.

And in supporting the end of a key provision of the Voting Rights Act that applied to states and other jurisdictions with histories of discrimination, Kennedy was affirming the autonomy and dignity of states' rights to be treated equally, the argument goes.

Fitting In

Rosen says that he views Kennedy as the only justice "willing to pursue this libertarian vision on the left as well as the right."

On the left, he says, Justice Sonia Sotomayor "seems most committed to expansively deciding cases involving dignity."

On the right, he says, "Justice Clarence Thomas is the most passionately committed to liberty in the realm of property rights and limits on federal power, but is less willing to strike down morals legislation supported by social conservatives."

And that's why, according to Rosen, "Justice Kennedy is the most activist judge on the court — willing to strike down federal and state laws when they violate individual liberty and dignity."

Even if, as Scalia wrote in his DOMA dissent Wednesday, the action is simply " ."

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAxNDQ2NDAxMDEyNzU2NzM2ODA3ZGI1ZA001))