Coronavirus ripped through First Baptist Church in the city of Sterling, the seat and semi-urban population center of Logan County in October. but Pastor Mark Phillips knows of at least thrice as many cases among his congregation and their relations.

When the pandemic began in earnest, Phillips hired a part-time employee solely to keep surfaces sanitized and ensure seating remained at a six-foot distance. Among many other efforts, the church also created extra services and meetings to reduce the number of people in attendance simultaneously. Mask wearing has been optional.

“So where it would have come from, I can't tell you,” Phillips said. “Do we feel like we did something to inflict it on us or the community? I would say no.”

Logan is a small rural county (population 22,409 including about 2,000 inmates in the state correctional facility), in Colorado’s northeast corner. In some ways, Logan has been Colorado’s canary in the COVID-19 coal mine. It was home to one of the earliest, large-scale outbreaks and months later it wasNow, it's among the first counties to be

“It reflects in our data that we’re not social distancing as much as we should, probably having too many gatherings, maybe not wearing face coverings when we go out,” said Trish McClain. She’s director of the Northeast Colorado Health Department, which manages Logan and five other nearby rural counties.

Colorado is now seeing a dangerously high spike of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths, even in rural Logan County. At one time, rural areas are safer from the coronavirus due to their low, spread out populations and should not be subject to heavy restrictions as a result.

Area residents say living in a hotspot can be scary, stressful and divisive — sharing their thoughts in interviews and on a community Facebook page, I Care Sterling #2 (the first was shut down earlier this year after moderators decided they couldn’t handle the polarized posts and angry users anymore).

On one extreme, some are against all the public health restrictions, going so far as to doubt how dangerous or real COVID-19 is. On the complete opposite end, others are upset that heavier restrictions were not put into place sooner, with some wanting a full lockdown.

In August, found around half of all respondents statewide were willing to delay the reopening of businesses if it meant shortening the pandemic and reducing deaths, while around a third wanted to reopen entirely. In an almost exact reversal, half of all rural respondents (11% of all 2,275 polled) wanted to reopen entirely while just over a third wanted to delay. Many rural respondents (40%) supported mask requirements to some degree, but at a level lower than the rest of the state.

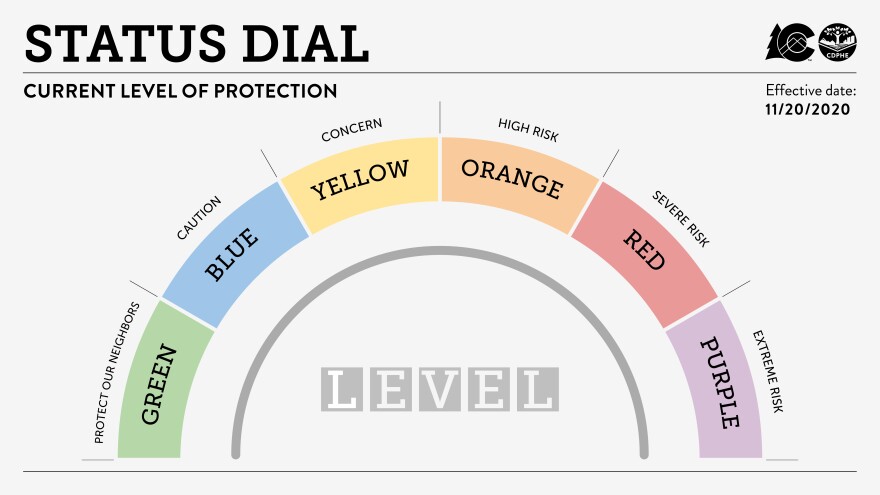

Under Safer-At-Home Level 2, Logan County churches and restaurants could open at 50% capacity among other restrictions for various sectors. Under Level 3, which the county moved to at the beginning of its spike, capacity allowance dropped to 25%. NCHD director McClain at the time hoped the shift to Level 3 would bring Logan County’s spike to a halt.

“People are still engaging in activities with people outside of their households, however with the colder weather more gatherings are moving indoors which carries a higher risk of transmission,” she said.

And so, with the number of new cases still growing, the county was moved to the new “red” level, under which churches can still allow 25% capacity but indoor dining is totally off the table.

“We're really trying to rely on people to do the right thing,” she said. “That always makes it a little more challenging because there are those that, for whatever reason, choose not to. And that can be very frustrating to all of us.”

McClain is not the only local official to place blame on individuals and private social gatherings for the spike. The clearest example of this is a

Steven Smith, NJC's vice president of student services, said the 47-case outbreak was tied to an off-campus party. Since the outbreak's start in late October, there haven't been many new reported cases tied to the college.

“We had a tough time of it for a while and now we're good. But now the county is struggling a little bit with the case positivity,” Smith said. “Because of the change on the dial for Logan County, Northeastern Junior College had to tighten up our restrictions as well to be in compliance with what's going on in the county. So that was unfortunate.”

Currently, only classes that are very hands-on, like welding and cosmetology, are still happening in person, he said. The rest are back to virtual.

Living the numbers

When Pastor Phillips heard about the first two cases among congregants, he contacted health authorities about a possible outbreak and willingly chose to shut down all church activities for about a week in early October. Despite these efforts, he ended up getting a bad case of the virus himself.

“I felt like someone ran me over with the truck, backed up over me to make sure that they ran over me with the truck. I mean, you just felt there was nothing left. You were plain beat up,” he said.

The worst symptoms lasted about a week. Never so bad that he needed to be hospitalized, but bad enough that his doctor ordered him to use the oxygen machine he happened to already have at home. He continued to record video services from home.

“And so I'd have all my energy poured into an hour slot to do a whole church service,” he said. “And then I would sleep the rest of the day and sleep the next day, too.”

Phillips said the state will soon be removing First Baptist from its active outbreak list.

“I will say to you that by far the vast, vast majority of people have recovered, I don't want to say easily, but have recovered as much as you can recover,” he said. “But I'll be very honest, COVID is a crazy creature.”

In, though about possible long-term health impacts from the virus, even in short cases like Phillip’s. He used to only have to use his inhaler a few times a year, but since recovering from the virus he’s had to use it weekly.

Several congregants were hospitalized, he said. Two died with COVID-19 and another member lost close family to it.

“We are very saddened and saddened by their loss. But at the same time, that sadness is more for us,” Phillips said.

Do restrictions work?

Phillips takes the virus seriously, takes all the appropriate precautions like social distancing and masking. He believes others should too — just on their own terms.

“The problem is that (state officials are) not here, so they don't necessarily see what we deal with,” he said, adding that he appreciates the largely hands-off response local officials have taken.

Phillips also questions how effective these restrictions are in general.

“When you get out here in this area, inflicting things on people is not a very effective method of getting people to pay attention and to care about things,” He said. “Instead, they will see you as the enemy and everything good that you have to say to them is no longer good because they're not going to listen to you.”

“We were just getting to the point where a lot of people were starting to comply during that time,” County Commissioner Byron Pelton said, referring to the month between when the state warned the county about it being moved to a more restrictive level on the dial and when it actually did.

He cites what he personally sees people doing when going out in the county as his source for that belief. “And then when they moved us back on the dial, I don't know if that was the best thing to do with our community out here. I wouldn't say it hurt (compliance). It might have hindered a little bit,” Pelton said.

Other residents painted varying pictures of what they see in terms of public health compliance while doing things like getting groceries, working in retail and driving through downtown Sterling. NCHD said it lacks the resources to track compliance in any meaningful way, apart from the continued climb in the total number of cases both before and after heavier state restrictions were in place.

Pelton agrees that one person’s experiences are not enough to definitively say how well compliance is going at any one time. But either way, he doesn’t believe restrictions are right for the community.

“I think that having personal responsibility and leaving it up to them and just sending out the education, I think that's the best way to continue forward,” he said.

Beyond the importance of local-governance and worries about restrictions pushing people to rebel more, Philips looks at the counties across the state that put in heavier restrictions and are still experiencing a spike — along with the outbreak at his church despite all those precautions — and goes: “Now what?”

“There's nothing that tells me that it's stopping it,” he said. “Nobody is showing me evidence that it is all under control anywhere.”

The regional health department disagrees.

“We can’t stop the virus but we can certainly slow it down," NCHD director Trish Mcclain said in a written statement. "By not putting restrictions into place, we will overrun our health care system and then anyone, whether they have COVID or a heart attack or stroke or accident, will not be able to receive the care they need to survive. I’m not willing to get to that point without a fight.”

There is a lot of evidence that public health restrictions reduce the virus spread, which can mean fewer deaths and hospitalizations. One study in the examined 42,000 interventions across 226 countries and found lockdowns, curfews and closures consistently reduced infection rates. Studies found counties in and that opted not to require masks consistently saw higher infection and hospitalization rates.

Phillips' other big problem with these restrictions is the mental health impact, and he is not the only resident to bring it up.

“I shudder because I don't want to do more than the three funerals,” he said. “But I can see isolation becomes a horrible process and it leads many to just shutting down and no longer having the will.”

Based on what he sees in his work with "Celebrate Recovery," an addiction support ministry within First Baptist, Phillips worries about the community's mental state as the pandemic drags on.

“We have seen a huge spike in the addictive activities," he said. "A huge spike in people that are leaning more towards suicidal feelings and those kinds of tendencies from all of the isolation and separation that has been built around this.”

There isn’t much clear up-to-date data in Colorado on how many suicides and drug overdoses have been happening since the pandemic’s start. However, about 40% of rural residents in reported increased anxiety, stress or loneliness related to the pandemic (53% statewide).

More restrictions, please

Michelle Lee teaches at Northeast Junior College. She worries about her students’ mental states now that most in-person classes have been moved back online due to the community spike.

“It's very difficult, it's not ideal, it's not how we were designed,” she said.

Lee believes there have to be ways to support community mental health while reducing direct contact.

“We were just getting in the spring to where we were getting some really good ideas on how to cope with that better,” Lee said. “And then summer came and now we were back to normal. So I think maybe we need to look at that more long-term. And I don't know how to do that.”

No matter what, Lee doesn’t think the benefits of more direct contact are worth risking other people’s physical health.

“I know people that have died from it,” she said. “I had a friend from high school in the Front Range die of it in the spring. It's not OK.”

She, like the local officials who spoke to KUNC, blames individuals refusing to follow public health guidelines for the spike and believes the county government should have taken stronger action, sooner.

“I feel like the residents of Logan County maybe and the local government don't take it seriously enough,” she said. “That people are not doing what they need to do to keep themselves and this community safe.”

Lee supports heavier restrictions because they reduce opportunities for virus spread. The county’s annual “,” for example, typically takes place on a crowded main street. This year, however, floats will sit in a park while spectators drive through.

“Nobody can make me wear a mask. That's going to come out of the kindness of my heart,” she said. “But we can, as a community, change the parade. We can make you do things different.”

Division over virus precautions is just as present within the walls of her home as they are outside.

"He takes more of the political view that it's for political reasons for being asked to wear masks,” she said, referring to her 20-year-old son who declined to be interviewed for this story. “Where I don't see it that way so much. I think it's more of a scientific reason.”

They discuss this disagreement often and both minds always remain unchanged, which Lee is fine with. But if it becomes necessary, she’s willing to ask him to keep his distance.

“That's going to be a difficult conversation, but definitely to protect my own health and to protect the health of other family members, that's the way it's going to be,” she said. “My take on it is I have an elderly mother and I want to protect her.”

Residents said they have different approaches to friends, family and fellow community members who disagree about public health precautions. Some just leave it alone, while others, like Hannah Johnson, tackle their views head-on.

“I have family members and really close friends that have immune system issues, immune deficiencies. My grandpa was told that if he catches it he's going to die,” Johnson said. “So I'm just like, I would rather people be mad at me and maybe get a little bit of information and think for a second.”

There’s still room for nuance

More than 10% of both rural and statewide respondents in the said they either wanted the state’s economy to “both” or “neither” fully reopen and delay reopening or replied with “don’t know/NA.”

“Much as I want my business to grow, I don't want I don't want the cases to grow as well,” said Nathalie Bejarano.

On one hand, she’s taken quite a hit economically since the start of the pandemic. For the first few months, she worked multiple jobs and several small side gigs to barely afford necessities and keep making payments on equipment she and her husband leased for , a business they started in August 2019.

“To be honest, it was very hard,” she said. “I understand I was not the only one going through all this, but sometimes you just have to make it work.”

She’s right about not being alone: other residents said they lost a job because of the pandemic. In the 31% of statewide respondents experienced a reduction in their working hours and 19% were laid off.

On the flip side, one resident said they left a job at Walmart because the risk of catching the coronavirus was too great. 19% in the poll said they had “been required to go to work” despite “health and safety concerns.”

Since Logan County opened back up over the summer, Bejarano's carpet cleaning company started to hear from clients again and was able to get back to almost breaking even. She’s not sure how her family and that business could economically survive another lockdown.

On the other hand, she also sees people in her community disregarding public health recommendations. And she is diabetic, which puts her from a COVID-19 infection that she’s already seen too much of.

Her grandfather got the virus in April and died a few days after being put on oxygen. And it seems that at his funeral, someone gave Bejarano’s father the virus too. He made it through after a long and difficult hospital stay, though he lost a lot of weight and still is very fatigued.

“I have been on both sides,” she said. “You are a business owner and you're against a lockdown or you experience COVID (in your) family and you do want to lockdown.”

Further complicating things, she’s not sure this new “Level Red” is better for her business than a straight-up lockdown.

“If I'm going to lose clients, then might as well just lockdown and let's try to pass this as soon as possible," she said.

Bejarano is still torn about what she wants to see happen, but wonders if there's another way this could all go.

“I would say that if we do believe that the mask works and maybe more social distancing works then, maybe we should try and do it,” she said. “For the sake of our health, for sure, and also for our business.”