In March, Mya Hunter sat in a hotel room in Miami. She had just finished a long day of training for the . The next morning, the recent Colorado State University graduate flew to Jamaica to begin her work as an agricultural volunteer with small-scale farmers and fulfill a desire she has had since she was a young girl.

“I am so excited,” she said. “I think if you asked me this like 48 hours ago, I would be super, super nervous.”

The 22-year-old Korean Hawaiian was born and raised on Oahu where her mother's family has lived, along with other islands, for generations. She said the natural resources there have shaped every part of her life and made her decision to join and work with the Peace Corps an obvious transition as she focuses more on future goals involving agriculture on the Hawaiian islands.

“I really hope to learn as much as I can from it [the Peace Corps experience] so that I can bring all of that knowledge and wisdom back to Hawaii one day and can help to improve ag back there,” she said.

Hunter is one of over 1,300 Americans currently serving in 53 countries across the globe. As a CSU alum, she is also part of a Peace Corps history that dates back over six decades.

CSU plants seeds for Peace Corps

In 1959, the idea of an international youth service program, called a “4-Point Youth Corps,” was making its way through congress. The following year, lawmakers passed a bill authorizing a study to determine if such a program was possible. That’s where CSU comes in.

“The Peace Corps wasn't founded at CSU,” Jane Albritton, former CSU faculty member and Returned Peace Corps Volunteer (RPCV) who served in India in the late 1960s, said. She was the lead editor for four books of stories written by RPCVs published in 2011 to celebrate the agency's 50th anniversary. “But something of its spirit and optimism is rooted here.”

CSU Research Foundation director Maurice “Maury” Albertson won the $10,000 federal contract despite fierce competition from other universities like Stanford and MIT. He studied water resources and mechanics which in international research and development in Southeast Asia. He frequently traveled to Washington D.C. and heard about the 4-Point Youth Corps.

“His antennae picked up on this buzz of a youth corps doing something internationally,” Albritton said. “He was committed to international connections and educational cooperation.”

The contract called for a detailed study of how the youth corps would work in at least 10 countries on three continents. It was a tight deadline. Alberston went to South Asia and asked another faculty member, Manuel Davenport, who was teaching in Africa to conduct the study there. He recruited his colleague Pauline Birky-Kreutzer, who helped him write the proposal to get the contract, and sent her to South America and the Caribbean.

“Morey was the big ideals guy and Pauline was the detail person,” she said. “You really can't have the big idea without the details working out.”

In late February, 1961 Albertson and Birky-Kreutzer issued a report that confirmed a Peace Corps program was possible.

On March 1, 1961, President John F. Kennedy signed an Executive Order that established the formation of the Peace Corps on a temporary, pilot basis. He then instructed Congress to create a new permanent agency. The Peace Corps would allow U.S. adults to serve their country and the world.

“I’m hopeful that it will be a source of satisfaction to Americans and a contribution to world peace,” Kennedy said in his address.

By August, of volunteers arrived in Accra, Ghana to serve as teachers. Less than a month later, Congress passed the , with a mission to “promote world peace and friendship.”

Over 240,000 Americans have served in 143 countries since the Peace Corps’s inception in 1961. That mission continues today.

“World peace and friendship is not the mandate exclusively of politicians and governments. It is about all of us. It's about building relationships across borders, across difference, about coming together in community and living and working side by side,” Peace Corps Director Carol Spahn said at a recent event at CSU.

Despite this country’s long commitment to international service there isn’t a monument or museum dedicated to the agency and volunteers.

Honoring the legacy

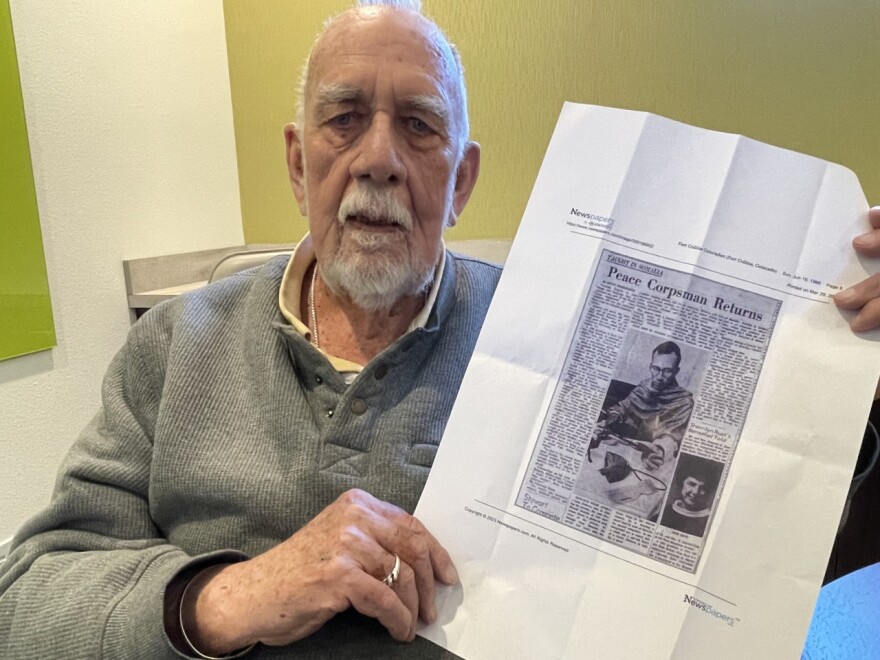

John Roberts was raised in Fort Collins and attended the University of Colorado Boulder to study international affairs. In early October, 1960, he met then presidential candidate Kennedy on campus during a campaign tour. He remembers Kennedy talking about an international service corps. This visit occurred before Kennedy’s stop at the University of Michigan where he proposed the establishment of the Peace Corps.

Growing up, Roberts knew Albertson and dated his daughter in high school. When he was at CU Boulder, Albertson was creating the Peace Corps feasibility study and would run ideas by Roberts.

“He'd call me at CU Boulder every weekend to say, “I want to bounce this off you,” he said. “As they had five weeks or six weeks to put this together, I sort of felt involved.”

Roberts graduated in June of 1964 and immediately went into the Peace Corps. He served as a teacher in a rural village in Somalia. He arrived in the East African country excited but also wary and unsure.

“They told us that we would not be in contact with our families for two years,” he said.

He had never taught before and was tasked with instructing boys in several subjects including biology. He remembered one lesson involved dissection and the students brought him a little antelope to work on. He cut into the dead animal and, not realizing it needed to be drained, it exploded all over him and many of the students. He pulled out the heart, lungs and stomach.

“I had no idea what I was talking about, but these kids had never seen anything like it,” he said. “They loved it.”

Roberts survived and even thrived. The experience had a profound impact and when he returned to the States, he forged a career in international service. Roberts worked in the Foreign Service for decades before returning to the Peace Corps as a country director. After retiring, he taught international studies at CSU. He traveled the world and spoke nine languages.

The Peace Corps taught Roberts most of things he knows today, he said.

“To be resilient, to work with people, to be patient, to try to be tolerant, to be accepting and to be curious in order to survive overseas, anywhere as a foreigner,” he said. “Peace Corps is the greatest invention that our country ever put together for international understanding and for international work.”John Roberts, Peace Corps volunteer and Country Director

“To be resilient, to work with people, to be patient, to try to be tolerant, to be accepting and to be curious in order to survive overseas, anywhere as a foreigner,” he said. “Peace Corps is the greatest invention that our country ever put together for international understanding and for international work.”

Roberts believed the agency needed to be recognized and two decades ago set out to create a memorial at CSU. With a group of RPCVs and university administrators, they raised enough money to achieve this dream.

In March, the university held a groundbreaking ceremony for a Peace Corps Tribute Garden. During the ceremony CSU President Amy Parsons said the garden will serve as a record, a reminder and an inspiration to future generations.

“It’s about the future as much as it is about the past and honoring those giants,” she said. “We hope that it will be a place that all of the Returning Peace Corps Volunteers can come and gather and share their experiences.”

When it’s completed in the fall, the thousand square foot Peace Corps Tribute Garden will be located just west of the Lory Student Center Theater with a sweeping view of the Rocky Mountains. It will feature a spiral walking path surrounded by native plants, benches for people to reflect and an outdoor classroom. The garden will tell the story of CSU’s rich Peace Corps history.

Jennifer Solomon, an associate professor at CSU in the Department of Human Dimensions of Natural Resources, is one of dozens of RPCV who work at the university. She thinks the garden is a great idea.

“(I) hope that it will inspire students to actually join the Peace Corps,” she said. “CSU, we’ve been really successful sending lots and lots of students to the Peace Corps.”

In 1995 when Solomon was in her early 20s, she served as an environment volunteer in Nicaragua. She worked for a Dutch funded non-governmental organization that focused on integrating conservation issues into the national curriculum with the Ministry of Education. She created materials for elementary through high school teachers to use throughout the country.

“We had lots of games and activities for teachers to do,” she said. “We produced a book that described all of the activities that could be done for different subjects, and that was delivered to teachers throughout the country.”

Solomon lived in the central part of Nicaragua and became very integrated with people in the community. She found out about their lives and through conversations came to understand how the environment and conservation affected them. As a Peace Corps volunteer she was there to support them but says she gained valuable knowledge as well.

“Often the folks who you work with already have tremendous knowledge and you're learning a lot of information from them,” she said. “It's a real gift, really, what they give to us as Peace Corps volunteers.”

The call to serve continues

Now in Jamaica, Peace Corps Volunteer Mya Hunter will spend the first three months at the training facility before relocating to her permanent location. Her cohort includes 20 other Americans that range in age from early 20s to mid-60s and come from all different backgrounds.

“It's an incredibly refreshing feeling to be with these people and have their support and encouragement and learn from them,” she said.

She’s about two months in and is learning farming techniques around water conservation and drought mitigation. They are growing vegetables like Callaloo and Pok Choi in a three-tiered garden and have planted coconut palm leaves to shade the crops.

Hunter said her days start early and are packed with things to do. There are daily devotionals, Patois language and Jamaican cultural lessons, and agricultural training. Then she goes home to her host family. She’ll wash her laundry by hand, study and play with her younger host brother.

“(The days are) all getting filled up with really good things,” she said. “Just being tired. Personal space and alone time is not culturally as a thing like here as it is in America.”

Hunter will be the first Peace Corps Volunteer to be stationed in Saint Andrew Parish in the Blue Mountains. She’ll work with a farmers group to learn how they grow crops and help them mitigate the effects of climate change to achieve their goals.

“I imagine it'll be very exciting and a little scary. And that will probably level out and then become more comfortable,” she said.

Hunter is part of a long line of CSU grads who have traveled the world to make a difference. Their history and contributions—as well as those from thousands of others who’ve served—will be celebrated for generations to come at CSU’s Peace Corps Tribute Garden.

A sad post-script to this story. John Roberts, a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer from Fort Collins who helped spearhead CSU's Peace Corps Tribute Garden, died last week. Roberts was proud of his time in the Peace Corps, and he told reporter Stephanie Daniel that he took particular pride in the role CSU played in the Corps’ creation and history.