For Fort Collins-based photographer Elliot Ross, the camera has always been a way of finding comfort, ever since coming to Colorado from Taiwan.

"When I moved here, I was 4 and incredibly shy," Ross said. "It was a big transition moving from Taipei to a very rural situation. And my grandma gave me a camera. She thought maybe that might help ease some of that anxiety. And it certainly did. It became a fixture of my daily life."

Much of now focuses on creating conversations where they may be lacking, and to provide others a place to share their stories. During the 2016 presidential campaign, Ross found a new conversation that he felt needed to be told.

That's where his latest exhibition "American Backyard" began. Now on display at the , the show looks at the people and places along the U.S-Mexico border and the wall that separates us — both literally and figuratively.

"This idea got started, I guess through my curiosity as to why (President) Trump's message was so intoxicating specifically with the evangelical base," Ross said. "A man that represents so many character traits that are directly in opposition to what it means to be a Christian. I wanted to get to the core of that, and the border wall and the border issue was a really emotional aspect of that."

He and his partner, writer and artist , traveled to Trump's inauguration, talking with hundreds of supporters to find out why they felt the wall was important and how that factored into their decision when it came time to vote.

"None of them had been to the border," Ross said. "None of them had a relationship to the border, but it was in their top three reasons for almost all of them."

So, Ross and Allison decided to visit the border and meet the people who live near the wall. They thought the project would take about six weeks. They ended up traveling the border for five months, starting in Brownsville, Texas and working their way to Friendship Park in San Diego.

With the aid of the Department of Homeland Security, they followed the border easement, trying to stay as true to the actual demarcation as possible, Ross said.

Finding subjects to interview and photograph came from reaching out to educational institutions and nonprofits, any community related organizations, even posting on Craigslist for people who might have stories they wanted to share about life on the border. They also found a lot of their subjects just by happenstance.

"Other than that, it was a lot of just meeting random folks at gas stations, hardware stores," Ross said. "We were broke down quite a bit, so we were in places of vulnerability a lot of times, which — it's wonderful how hospitable and friendly and open most people are."

People like the store clerk who tactfully let Ross know he might need a shower (he and Allison slept in their car for most of the project) and then invited him to come to his home to get cleaned up and have a meal. That meeting turned into a friendship — and a photo.

In the Fort Collins exhibit, one of the first stops is a striking photo of a teenage girl, standing in front of a curved portion of the border wall, wearing a very big, very pink dress.

"When we first went to their house, the quinceañera dress was just hanging there right in the middle of the house," Ross said.

The dress belonged to Jaymin. It was her from her quinceañera, a Mexican rite of passage for girls. She showed them photos from the event, stored in custom-made, patent leather photo albums, and a DVD featuring footage of the entire night.

"Clearly still just the largest part of this young lady's life and she was just so proud of her big day that she had just had," Ross said.

Jaymin was born a week before 9/11. Ross was intrigued by the fact that her entire life had been spent in a post-9/11 world of heightened security.

"For her, it's just the texture of daily life, despite the fact that they live two blocks from the wall," he said. "I asked her what she thought of it, and she said she didn't ever think about it. She never noticed it. It was a part of the background. And that taught me something, I think it was a realization that made me a little scared and that was one of how easily these symbols of division and this heightened state of militarization can become so easily accepted and normalized, and all it takes is just one generation."

Overall, the reactions Ross received to the project were varied, but one of the most common was actually fatigue. What is broadcasted in the headlines isn't necessarily people's stories or the things important to them, he said.

"That's access to education, access to health care and basic things like sanitation," Ross said. "These things that most of us in the rest of the United States take for granted. But you have to remember that so many of the communities along the border are amongst the poorest in the country where, in some instances, two-thirds of people are living below the poverty line. And so when the government wants to build something that's incredibly expensive at the direct cost of their own public institutions, folks are a bit upset about that."

That gets addressed in "The Arbitrary Nature of Division no. 2." In the photo, two pickup trucks are backed up on either side of the fence, a series of steel pillars with wires strung between them. On the U.S. side is a man with an empty truck bed, and on the other side are three men, with a truckload of hay and supplies.

The fence goes right through the Tohono O'odham Nation, one of the largest reservations in the country. At the time the photo was taken, there was only one gate between the two sides, and the key to that gate was broken, Ross said. No one had jurisdiction to replace the lock, making the only gate unusable.

Due to the remote nature of the land on the Mexican side, the people there rely heavily on those from the north side to bring supplies to the fence.

"And under the supervision of border patrol, handing over bales of hay, frozen chickens," Ross said. "And so that's what's happening (in this photo). They had just finished that transfer. And it kind of reflects just how … no land is designed to be separated by any sort of human fiction. And in this case, it has resulted in the disintegration of this once-whole land and these peoples that have called southern Arizona and northern Mexico home for thousands of years."

Ross was surprised to find during the trip that after speaking to more than 1,000 people along the border — roughly half of them conservative Republicans — only a couple of them were actually in favor of the wall.

"Maybe that was just our luck of the draw but I think that's revealing," he said.

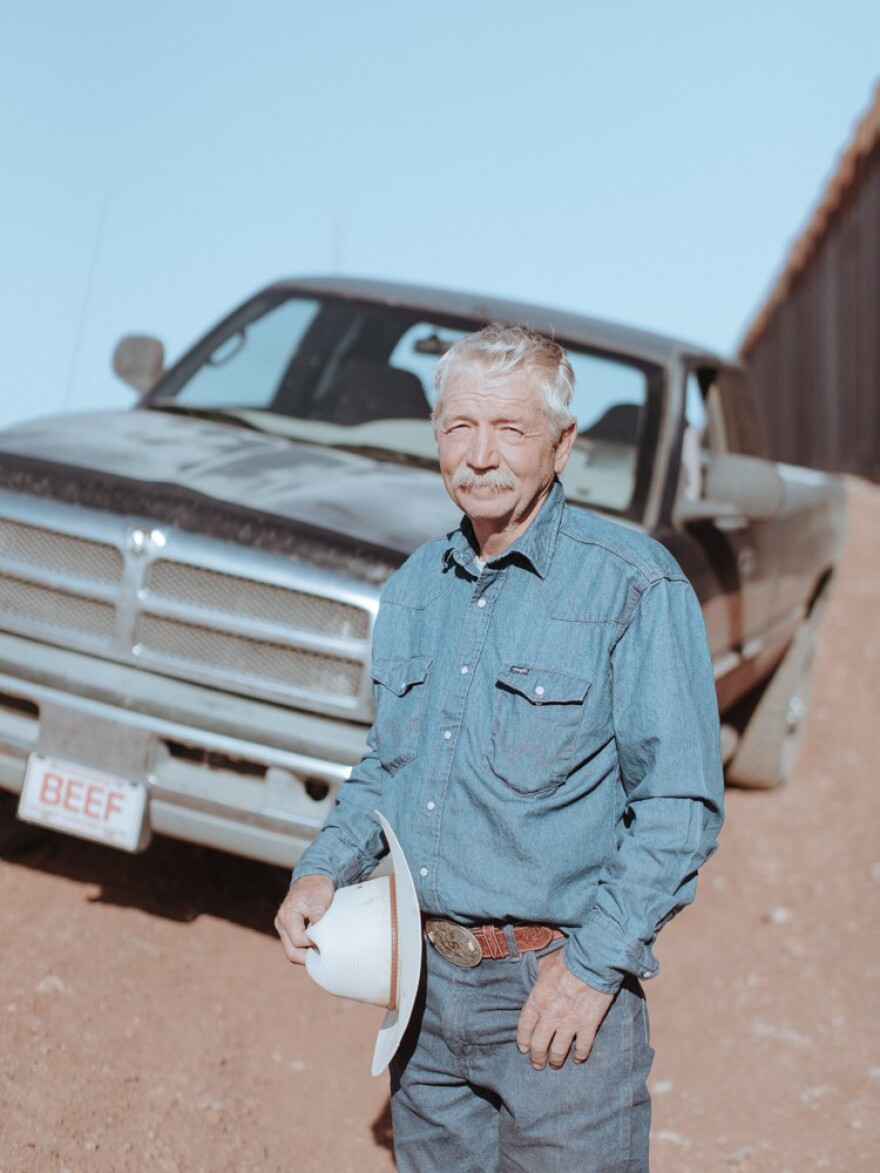

One of the most surprising opinions came from dedicated Trump supporter John Ladd, Ross said.

Ladd, a southern Arizona rancher who Ross photographed in front of his pickup truck with a license plate that read "BEEF," has taken part in civilian militia groups to track down people crossing into the U.S. illegally. At the time Ross spoke with him, Ladd wasn't sold on the border wall and its ability to protect his 16,000-plus acre ranch.

"Even this guy who represents some of the furthest right of the political spectrum, was against the border wall for a very fundamental reason, and that was the desire to limit the power of the central government and to limit federal overreach," Ross said.

Ladd has since spoken out about a need for a stronger mix of infrastructure and increased patrols.

Like the people who live there, Ross said the border itself is full of surprises. In some places, there are walls 20 feet high or more. In others, there are 300 meters of barbed wire fence with miles of open space on either side.

In one photo, there's a wall of corrugated metal, which is made of repurposed landing mats from the Vietnam War, Ross said.

"And it runs up on both sides to a boulder that's just in the middle," he said. "So this great force of infrastructural might has just been stopped by a rock. And I think it's a poignant symbol of just how arbitrary the nature of this infrastructure is."

On the last day of the trip, Ross was wrapping up at Friendship Park in San Diego and chatting with three border patrol agents when two white trucks pulled up.

"The agents are bristling a little bit because they're unauthorized vehicles, and we hear the weirdest barking coming from out of the back — not like a dog bark," he said. "Someone jumps out of the truck and opens up the back and three sea lions pop out and come waddling down the beach and that's when I noticed that the license plates said, 'SeaWorld1' and 'SeaWorld2.' And they were reintroducing sea lions right there at the Pacific terminus of this immense piece of infrastructure and it was just a very poetic way of summing up just how crazy this part of the United States is. It was a very beautiful moment and one of hope."

Regardless of how people perceive the border wall, Ross said he hopes that visitors to "American Backyard" go beyond the headlines and political divides and instead see the people who live there. It's one of the reasons for the show's name.

"We wanted to allude to the American dream, (and) some of these motivations for people moving north," he said. "And what's more quintessential than a white picket fence to put around your own backyard?"

"American Backyard" will be on display at the Museum of Art Fort Collins through March 15. The museum is also showing the exhibition "Shelter: Crafting a Safe Home."