The blue corduroy jacket worn by high school students in FFA, formerly the Future Farmers of America, is an icon of rural life. To the average city dweller the jacket is a vestige of dwindling, isolated farm culture, as fewer and fewer young people grow up on farms. The numbers tell a different story. In spite of that demographic shift, a record number of kids are donning blue jackets.

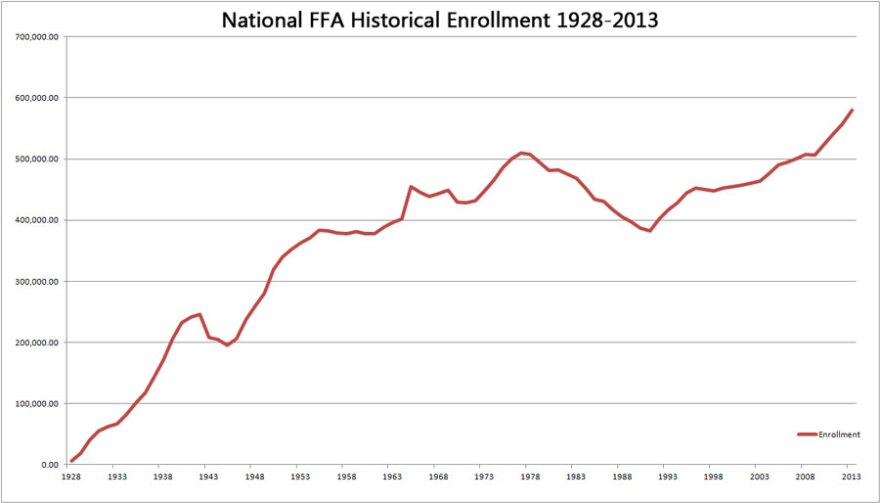

From 2007 to 2012 the U.S. lost almost 100,000 farms, according to recent census data. While during the same period FFA enrolled an additional 60,000 students, and opened new chapters, bringing the organization to its highest number of students in its almost century-old history, just shy of 580,000.

ThatŌĆÖs a lot of blue corduroy jackets.

Those involved with FFA tout the record enrollment as a testament to the organizationŌĆÖs nimbleness in the face of an increasingly urbanized society.

ŌĆ£The perception is that FFA is plows, cows and sows,ŌĆØ said , National FFA Organization CEO.

Instead of spending classroom time solely devoted to agrarian topics, chapters and school districts are choosing a more diverse curriculum. And the changing focus appears to be working. Inner city chapters in places like Chicago, Philadelphia and New York are some of the fastest growing in the country.

ŌĆ£Now we talk about not vocational agriculture, but the science of agriculture and the science of food,ŌĆØ Armstrong said.

In those technology and science-heavy topics, Armstrong said teachers can begin to point students on more stable career paths ŌĆō something that couldnŌĆÖt be said during the 1980s farm crisis. ThatŌĆÖs when enrollment numbers slumped, chapters closed, the name went from Future Farmers of America to National FFA Organization, and the groupŌĆÖs philosophy shifted to ŌĆ£adapt or die.ŌĆØ

ThatŌĆÖs evident in agriculture instructor Lauren HartŌĆÖs classroom in Longmont, Colo. It looks out onto the St. Vrain Valley School DistrictŌĆÖs working farm, where students get hands-on learning with cows, chickens and pigs.

"It's always been blue corduroy, same emblem and everything."

Move inside the classroom walls and lessons include law, policy, entrepreneurship and bookkeeping, all with an agricultural touch. When sheŌĆÖs , Hart said she tries to reach further into areas you wouldnŌĆÖt typically associate with farming.

ŌĆ£The interest and the ability both of students going into production agriculture is declining,ŌĆØ Hart said. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs just not something that a high school student either wants to or thinks they can get into.ŌĆØ

Since sheŌĆÖs been teaching agriculture for eight years and was part of a Colorado FFA chapter when she was in high school. In that time, Hart said sheŌĆÖs noticed a shift. A greater number of students are interested in contemporary food trends, wanting to know more about organic foods and cage-free, grass-fed meat. Hart said she canŌĆÖt just ignore what students want to learn about.

The millennial generation is one step removed from the farm and their interests are different notes Kenton Ochsner, ColoradoŌĆÖs FFA advisor.

ŌĆ£The industryŌĆÖs changed,ŌĆØ Ochsner said. ŌĆ£And our students have changed.ŌĆØ

ThatŌĆÖs why many school districts and their affiliated FFA chapters are going to great lengths to make agriculture appeal to more students.

ŌĆ£Now, itŌĆÖs the hot topic. And parents in town want their sons and daughters to feel the land and to feel soil between their hands and to have an understanding of where their food comes from,ŌĆØ Ochsner said.

The pitch worked on 18-year-old Reece Melton, St. Vrain Valley FFA president. While his family has agricultural roots, he grew up in nearby Erie, Colo. Being one generation away from the farm is a common theme among the 60 other students in his chapter.

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre in an urban area, so most of our members do not grow up on property, though they still have that connection to agriculture,ŌĆØ Melton said.

Other with dramatic social change over the decades. Even though FFA is enjoying a resurgence after the 1980s farm crisis, itŌĆÖs still felt some growing pains as it figures out what students actually want to learn about and whatŌĆÖs still relevant.

A group like FFA brings in new blood on a yearly basis. Most active members are younger than 22 years old. That youthful energy gives FFA an edge over other rural, farm-related organizations, said , who studies agricultural education programs at Colorado State University.

ŌĆ£There are success stories and then there are maybe not so successful stories, and I donŌĆÖt want to call it failure, but itŌĆÖs sort of a struggle to adapt,ŌĆØ Martin said.

ItŌĆÖs about finding an appropriate balance between new ideas and old traditions. The most visible tradition in FFA is the blue corduroy jacket, a symbol of pride for students who spend enough time in the organization to earn one. ItŌĆÖs an enduring tradition as well, never changing through the years said Samuel Johnson, St. Vrain Valley FFA treasurer.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs always been blue corduroy, same emblem and everything,ŌĆØ Johnson said.

A static symbol of tradition in an organization thatŌĆÖs been forced to adapt to stay relevant.