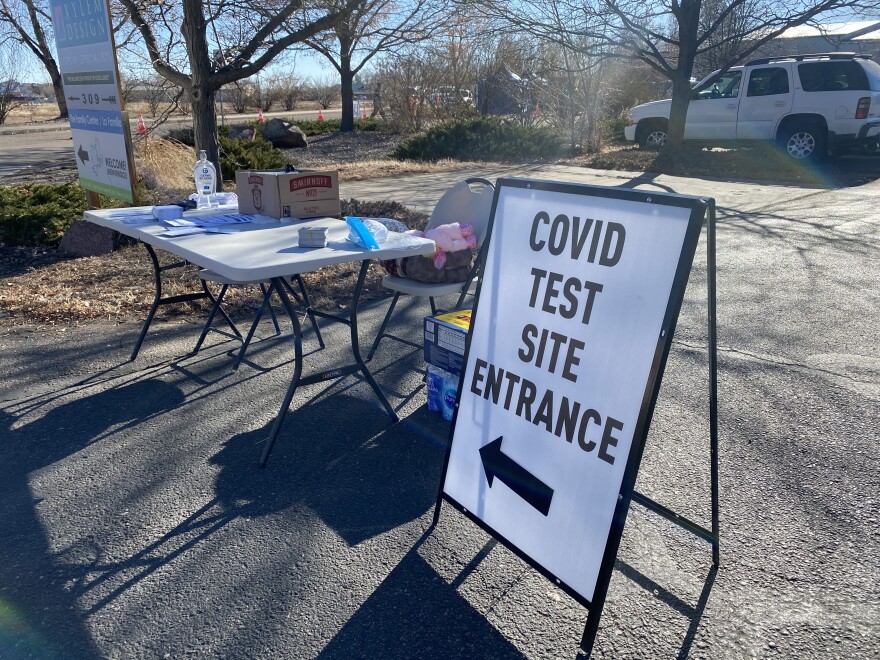

A silver van pulls up to a coronavirus testing site in the parking lot of La Familia, a daycare and family services center in Fort Collins. Cristina Diaz and her coworker hand fluffy, pink unicorn stuffed animals to the kids in the backseat. They load boxes of rice, milk, and masa flour into the back.

DiazŌĆÖs big brown eyes peek out above her black face mask, which has ŌĆśCristinaŌĆÖ written across it in red cursive. She oversees Larimer and Weld Counties as the regional coordinator for . These ŌĆśpromotoresŌĆÖ ŌĆö community health liaisons ŌĆö educate Latino residents, mostly Spanish-speaking migrant workers, about COVID-19.

In the past, to reach underserved communities on issues from smoking cessation to cervical cancer. Through , and the , this group launched in September to get the word out on virus prevention and care.

Promotores oftentimes lack formal medical training, but they are well-connected in their communities. Diaz, for example, has served on the boards of Northern Colorado nonprofits. Until recently, she was a social worker. Today, her strategy is to first draw people to the testing site with food boxes.

ŌĆ£And then say, ŌĆśHey, by the way, we have COVID testing right here. Do you have any of these symptoms? Do you know anyone?ŌĆÖ So they're going to leave here and they're going to go home like, ŌĆśHey, I just went and got this food box and I got tested.ŌĆÖ And then we're going to have more people here this afternoon,ŌĆØ Diaz explained with a laugh.

Going where people live and work

Working conditions, living situations and language barriers are among several factors that have led to . These promotores are stepping up to educate people who have not been reached by mainstream information sources.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs overwhelming as an English speaker,ŌĆØ Diaz said. ŌĆ£So I can even imagine, you know, as a Spanish speaker and even though Spanish speaking, not all of them tend to be literate. You can't just be like, ŌĆśOh, here's a form. Read this, you know, share it with your family.ŌĆÖ If they are sharing it with their family, they're probably sharing it with their 8-year-old or 12-year-old. And then all of a sudden, it's the job of the 12-year-old to educate the family on it.ŌĆØ

Promotores across the state are providing workers with winter clothing, masks and hand sanitizer by going to where they live and work: farms, warehouses and mobile home parks, for example. Project Protect Promotora Network has worked with the CDPHE on COVID-19 testing events, as was the case at the site in Fort Collins.

In their work, these promotores hear about needs that go beyond the coronavirus, relating to internet access, childcare and housing. In addition to language and literacy barriers, many Spanish-speaking workers are scared or distrustful of the government.

ŌĆ£You donŌĆÖt know how to ask for help so you prefer donŌĆÖt do it,ŌĆØ explained Soraya Leon, a promotora who lives in Greeley, in the county.

At the testing site in Fort Collins, wearing two masks and a face shield, LeonŌĆÖs breath fogged up the clear plastic shield; condensation dripped down the inside.

As a promotora who began doing this work in November, Leon has heard confusion and disbelief about the virus. But, when she talks to workers about it, she said they listen in part, because when Leon divorced her American husband, she became undocumented and needed help herself.

ŌĆ£I was there, I was in the same situation,ŌĆØ Leon said. ŌĆ£I know what you feel when you have issues.ŌĆØ

The Weld County Department of Public Health and Environment has worked with promotores in the past, but not specifically on coronavirus prevention. The department was unable to do a recorded interview for this story but in an email, a spokesperson outlined what they have done, from putting out messages on billboards, posters and social media, to interviews on Spanish-language radio.

ŌĆśI think it has contributedŌĆÖ

Dr. Mark Wallace, the former chief medical officer of Weld County, believes communication issues have contributed to the high infection rate among Latinos in Weld County.

"I think potentially, in the beginning, was more impactful, that lack of clear communication,ŌĆØ Wallace said. ŌĆ£I think it is less of that today since we've been struggling with this for as long as we haveŌĆ” So there is that fundamental level of awareness because we're doing a better job of communicating in a way that is linguistically and culturally aware.ŌĆØ

Wallace is now the chief clinical officer at Sunrise Community Health, a group of clinics in Northern Colorado; around half of their patients identify as Hispanic or Latino. He explains that since the beginning of the pandemic, the medical community has gotten better at talking through what terms like ŌĆśisolationŌĆÖ and ŌĆśquarantineŌĆÖ mean in daily life, for example. Now, he is beginning to think about the next communication issue: the vaccine.

ŌĆ£It's likely to have some similar challenges, I'm not going to be pollyannaish about it,ŌĆØ Wallace said.

around 60% of Coloradans are planning to get the coronavirus vaccine. Numbers were slightly lower among Blacks and Latinos. Wallace thinks it will be people like his bilingual medical assistants who will be most effective at getting the word out.

The next challenge? Vaccine communication

ŌĆ£I'd say if the Pope got a COVID vaccine, that would go a long way,ŌĆØ Dr. Michelle Barron, the senior medical director of infection prevention for UCHealth, said with a laugh.

She also hopes that her mom, who is from Mexico, will get the vaccine and then tell her friends.

ŌĆ£That would be the gossip. ŌĆśOh! Did you hear Nora got the vaccine? Oh, we should go get our vaccine too!ŌĆÖ... That, I think, is the power,ŌĆØ Barron said.

Barron said that community members and health workers ŌĆö like promotores ŌĆö are important pathways for information, but that this issue of communication is complex.

ŌĆ£The messaging that we're putting out there may work for 80% of our population, but what do we do differently for those 20%?ŌĆØ she asked.

At the state level, the CDPHE intends to reach marginalized communities through its initiative. The nonprofit Immunize Colorado launched a in September.

Both the CDPHE and Weld CountyŌĆÖs health department plan to work with promotores on vaccine education. Cristina Diaz, the promotora heading up the food boxes event in Fort Collins, expects the Project Protect Promotora Network will do this sort of work, but she predicts challenges.

ŌĆ£You know, it's hard to get them here just to do the COVID testing, so I canŌĆÖt imagine a vaccine,ŌĆØ Diaz said.

This is part two of KUNC's series, "Over-Infected, Under-Resourced: COVID-19 Hits Colorado Latinos Hard." Click here for more stories.